In this series, I will explore the notion of orientational order in random packings of anisotropic (flat or elongated), hard particles. By orientational order, I mean that particles which are close to each other tend to adopt the same orientation. This leads to strong local anisotropy, while the packing may well be globally isotropic; in particular, all orientations of single grains are equiprobable. Local orientational order is stronger when the volume fraction of particles, or their aspect ratio increases.

Local orientational order will be illustrated on a “real” packing, and I chose rice grains for this demo. Analysis of orientation correlations requires to go through the following steps

- acquisition of a 3D image of the packing through X-ray microtomography,

- segmentation of the 3D image (each grain must be labelled individually) by means of the Population C++ library,

- computation of the orientation of each rice grain, using the

scipy.ndimagePython module, - computation of the orientation correlations.

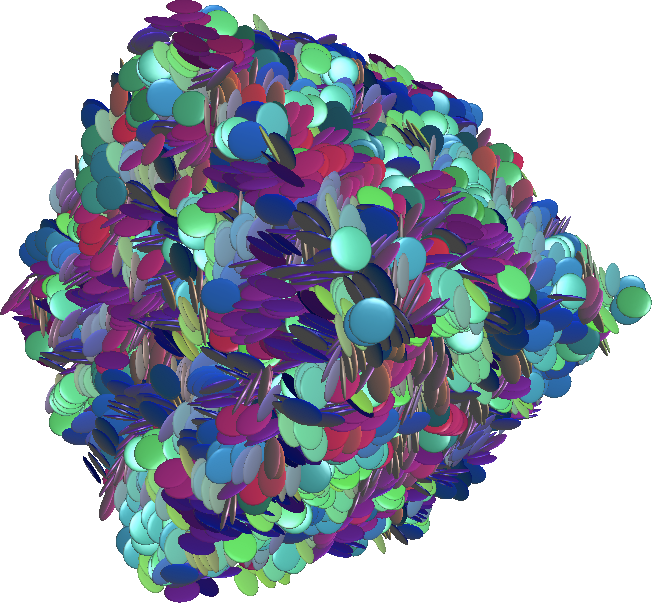

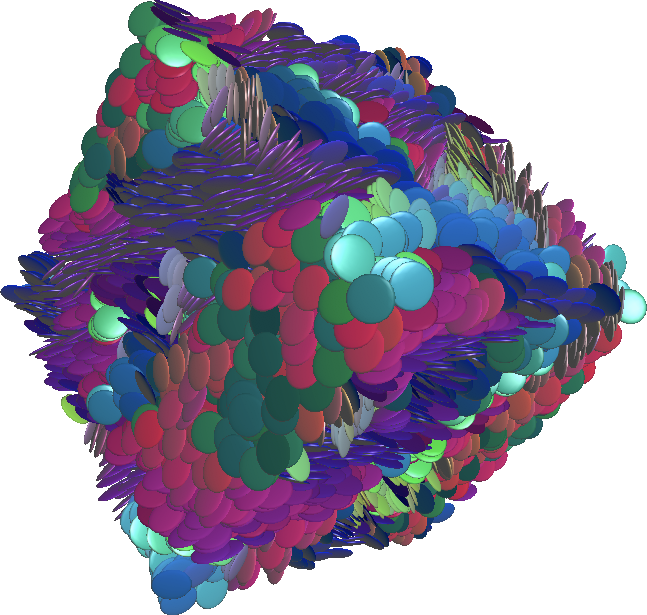

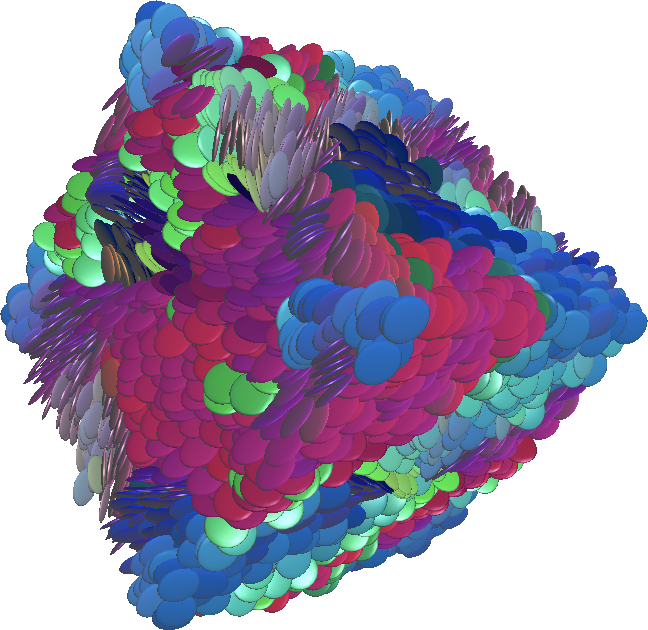

Before we proceed, I would like to clarify the notion of local orientational order through images of synthetic packings of 10000 hard (flat) spheroids. The aspect ratio (ratio of polar to equatorial radii) of the (flat) spheroids is 0.125. The images below (click to enlarge) are three realizations of random packing of spheroids, at 40% (left), 50% (middle) and 60% (right) volume fraction. The color of each particle is chosen according to its orientation, so that particles with similar colors have similar orientations.

|

|

|

It should be mentioned that generating such compact assemblies is no trivial task. The event-driven molecular dynamics algorithm proposed by Donev, Torquato and Stillinger (2005, 2005a) is an attractive option: it is both very general and versatile. It is however a bit complex, and I adopted a different approach, which we published a while ago with Pierre Levitz (Brisard and Levitz, 2013). In a nutshell, the microstructures presented above are the result of a kind of Reverse Monte-Carlo simulation with a non-physical pairwise potential. The interaction potential is zero when the spheroids do not intersect, and repulsive when they do.

It is observed that, as the volume fraction of particles increases, so does the size of the color patches. In other words, to pack the particles closely, you need to stack them! Mathematically speaking, the orientations of particles exhibit long-range correlations. In the next instalments of this series, I will show how these correlations can be quantified, both on synthetic and \"real-life\" samples.

See part 2 of this series.